INTERVIEW: Why one Holocaust descendant chose to become an Austrian citizen

For Howard Goodman, whose grandparents were killed in the Holocaust, taking up Austrian citizenship is "a way for me to explore half of who I am, the half I have little knowledge of".

Howard spoke to The Local during a two-month stay in Vienna, during which he has explored the city, including the places where his family lived.

"I didn't want to come and be a tourist. I wanted to get a sense of what it was like to live here, and I think I have. Vienna is not the same now as it was in the '20s and '30s, I can never know what it was like for my father, but I can get a sense," he says.

READ MORE: How descendants of victims of Nazism can apply for Austrian citizenship

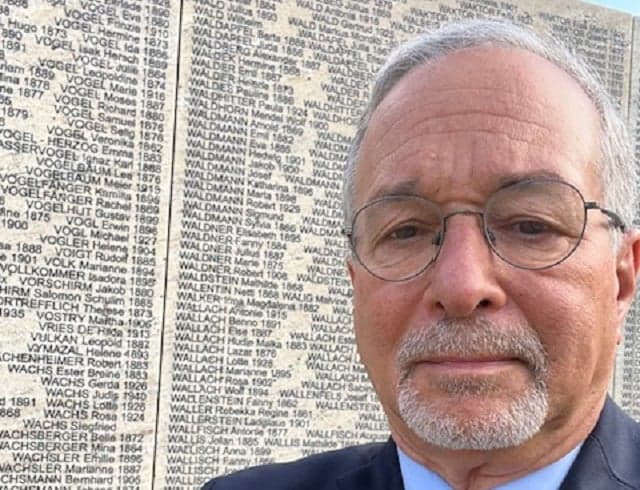

On Tuesday November 9th, Howard attended the inauguration of Vienna's new Holocaust Memorial, a Wall of Names featuring the names of thousands of Austrian Jews.

He was invited after taking up Austrian citizenship under a law introduced in 2019, which allows the children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren of those who fled the Nazis to apply for Austrian nationality without needing to give up existing citizenships.

Among the 64,000 names on the new memorial are two which mean a lot to Howard: his grandfather Emil Waldmann, and his aunt Livia Waldmann. The unveiling of the Wall of Names comes 83 years after Kristallnacht, violent attacks on Jewish synagogues, businesses and homes.

Howard's farther Armand was the only member of his family to escape the Holocaust, fleeing to the US with $2 and one steamer trunk. Armand got married and after an unsuccessful attempt to trace his family post-war, he tried to put his past behind him. At the age of 39, he died at home when Howard and his brother were aged two and five, with doctors linking the cause of death to the hard labour and beatings he suffered during internment in the Dachau and Buchenwald camps.

"This was very traumatic for my mother. She loved my father passionately and it was very painful for her to talk about him. I asked questions, but it would always upset her," says Howard, who changed his last name to Goodman after his mother remarried and his stepfather adopted him. He grew up knowing that his biological father was Austrian, but had little information beyond that and few objects from Armand's life in Austria.

Two of the items he did have included a 'Meldebuch' from what is now Vienna's Technical University, and a canteen with the word Budapest on it, and it was these that sparked his search for answers.

READ ALSO: ‘Walk with us’: Actors recreate Jewish flight through the Austrian Alps

It was only in 1998, with the internet opening up new possibilities for research, that Howard began to get some answers to the questions he had long had about his family. First, he realised that the book was not from a high school as he had believed from the name Technische Hochschule, but a university, and he was able to contact a webmaster from the university's website who shared more information.

The following year on his first trip to Vienna and his first time in Europe, Howard was able to get a copy of his father's diploma and discovered his grandparents' names after visiting the City Hall, which he says "opened up a whole new world" for him.

"It became much more real. It wasn't just that my father was from Vienna, but there was a whole family -- my family -- that had lived there. I learned that he had sisters. I learned that my dad was Viennese, but his family was really from the Hungarian side of the Austro-Hungarian empire, and moved to Budapest in the 1890s," he says. This explained the Budapest canteen -- his father likely would have travelled to the Hungarian city regularly to visit family.

It was Howard's brother who first found out about the possibility for descendants of Holocaust victims to apply for Austrian citizenship. At first, he wasn't sure whether to go for it or not, and spoke to his children about it.

"For them, the main appeal is that they could travel or move to Europe as EU citizens. For me, it's a way to honour my family's memory. I can't bring them back or change what happened, but it's a way of finding some completion and learning why I am the way I am," he explains.

"I have no feelings of anger or animosity towards Austrians. The ones who are here now are not the ones who did what [the perpetrators of the Holocaust] did. The fact that Austria offered this as some small act of restitution, I felt that it would behoove me in some way to acknowledge that."

Becoming Austrian isn't the only way Howard has chosen to honour his family's memory, and he has also spent time writing up his research into a book of family history to share with his own descendants.

Howard with granddaughter Livia, named after his aunt who was killed in the Holocaust. Photo: Howard Goodman

This includes information he has learned about the time his family lived in Vienna, photos of family members and their homes, and a family tree. He has found little information about his aunts, but knows that one of them, Elisabeth, died aged 20 while in Vienna's ghetto. His grandmother Hermina was taken into a sanitarium nine days after Kristallnacht, from where she was deported and murdered. Howard is now working to get Hermina's name added to the Wall of Names, though Elisabeth may not meet the criteria to be included.

"With a lot of the questions, I can hypothesise and make guesses, but many things I'll never know. I don't know if that's important. It's enough to have a general outline of their lives," he says.

READ MORE: How Austria’s newest citizens reclaimed a birthright stolen by the Nazis

Howard has had meetings with university archivists, leaders of the Jewish community in Vienna and others who can share details on what life was like when his family lived here. He has based himself in the second district, historically the home of Vienna's Jewish community and the location where Jews included his own family were relocated in 1938.

"There are things I can't begin to know. There is no record of what was destroyed or taken [during the pogroms], so did they lose their home, did something happen to them -- I can't begin to know, but I know the result was that they were moved to the second district."

While staying in the second district, Howard made a surprising and emotional discovery. He and his brother are the only known descendants of their grandparents, but he found out that there is already a small memorial to his family in their hometown.

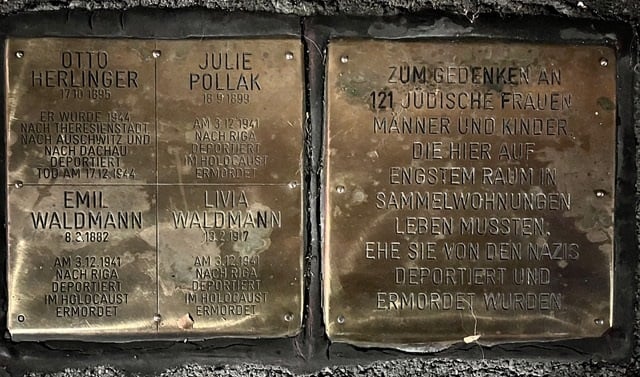

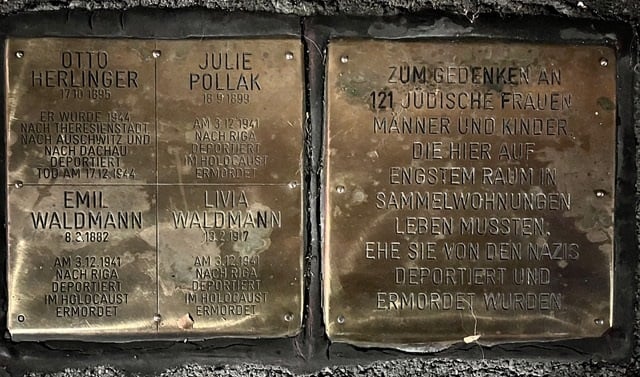

Outside the building which is their last known address, a small golden plaque -- one of thousands of Stolpersteine (stumble stones) which honour Holocaust victims across Europe -- notes that 121 Jews lived in the building. Just four of them are named, two of them being Howard's grandfather and aunt.

Howard's grandfather Emil and aunt Livia are named on the small plaque outside their last known address. Photo: Howard Goodman

READ ALSO: Stolpersteine: Standing defiantly in communities amid rising tensions

The stone was purchased by the daughter of another victim named on the plaque, an 86-year-old living in Germany, but Howard doesn't know why his family were included.

"I had been to every place I believed my family lived. I had been outside the building, crossed the street and taken photos, but never thought to walk up to the doorway," he says. "When I saw in the database that my family's names were there, I put on my coat, it was about 9 or 10pm, and walked over as quickly as I could. It was quite moving. I already knew where they had lived, when they were born, where they were deported to, but to see it physically like that was really quite an emotional experience."

As well as the Stolperstein, Howard's aunt Livia is remembered in another way: his youngest granddaughter is named after her. Under the new Austrian law, Howard's children and grandchildren are also eligible for citizenship.

"Preserving the Waldmann’s memory for my children and grandchildren is one of the reasons I’ve become an Austrian citizen," says Howard.

Comments

See Also

Howard spoke to The Local during a two-month stay in Vienna, during which he has explored the city, including the places where his family lived.

"I didn't want to come and be a tourist. I wanted to get a sense of what it was like to live here, and I think I have. Vienna is not the same now as it was in the '20s and '30s, I can never know what it was like for my father, but I can get a sense," he says.

READ MORE: How descendants of victims of Nazism can apply for Austrian citizenship

On Tuesday November 9th, Howard attended the inauguration of Vienna's new Holocaust Memorial, a Wall of Names featuring the names of thousands of Austrian Jews.

He was invited after taking up Austrian citizenship under a law introduced in 2019, which allows the children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren of those who fled the Nazis to apply for Austrian nationality without needing to give up existing citizenships.

Among the 64,000 names on the new memorial are two which mean a lot to Howard: his grandfather Emil Waldmann, and his aunt Livia Waldmann. The unveiling of the Wall of Names comes 83 years after Kristallnacht, violent attacks on Jewish synagogues, businesses and homes.

Howard's farther Armand was the only member of his family to escape the Holocaust, fleeing to the US with $2 and one steamer trunk. Armand got married and after an unsuccessful attempt to trace his family post-war, he tried to put his past behind him. At the age of 39, he died at home when Howard and his brother were aged two and five, with doctors linking the cause of death to the hard labour and beatings he suffered during internment in the Dachau and Buchenwald camps.

"This was very traumatic for my mother. She loved my father passionately and it was very painful for her to talk about him. I asked questions, but it would always upset her," says Howard, who changed his last name to Goodman after his mother remarried and his stepfather adopted him. He grew up knowing that his biological father was Austrian, but had little information beyond that and few objects from Armand's life in Austria.

Two of the items he did have included a 'Meldebuch' from what is now Vienna's Technical University, and a canteen with the word Budapest on it, and it was these that sparked his search for answers.

READ ALSO: ‘Walk with us’: Actors recreate Jewish flight through the Austrian Alps

It was only in 1998, with the internet opening up new possibilities for research, that Howard began to get some answers to the questions he had long had about his family. First, he realised that the book was not from a high school as he had believed from the name Technische Hochschule, but a university, and he was able to contact a webmaster from the university's website who shared more information.

The following year on his first trip to Vienna and his first time in Europe, Howard was able to get a copy of his father's diploma and discovered his grandparents' names after visiting the City Hall, which he says "opened up a whole new world" for him.

"It became much more real. It wasn't just that my father was from Vienna, but there was a whole family -- my family -- that had lived there. I learned that he had sisters. I learned that my dad was Viennese, but his family was really from the Hungarian side of the Austro-Hungarian empire, and moved to Budapest in the 1890s," he says. This explained the Budapest canteen -- his father likely would have travelled to the Hungarian city regularly to visit family.

It was Howard's brother who first found out about the possibility for descendants of Holocaust victims to apply for Austrian citizenship. At first, he wasn't sure whether to go for it or not, and spoke to his children about it.

"For them, the main appeal is that they could travel or move to Europe as EU citizens. For me, it's a way to honour my family's memory. I can't bring them back or change what happened, but it's a way of finding some completion and learning why I am the way I am," he explains.

"I have no feelings of anger or animosity towards Austrians. The ones who are here now are not the ones who did what [the perpetrators of the Holocaust] did. The fact that Austria offered this as some small act of restitution, I felt that it would behoove me in some way to acknowledge that."

Becoming Austrian isn't the only way Howard has chosen to honour his family's memory, and he has also spent time writing up his research into a book of family history to share with his own descendants.

Howard with granddaughter Livia, named after his aunt who was killed in the Holocaust. Photo: Howard Goodman

This includes information he has learned about the time his family lived in Vienna, photos of family members and their homes, and a family tree. He has found little information about his aunts, but knows that one of them, Elisabeth, died aged 20 while in Vienna's ghetto. His grandmother Hermina was taken into a sanitarium nine days after Kristallnacht, from where she was deported and murdered. Howard is now working to get Hermina's name added to the Wall of Names, though Elisabeth may not meet the criteria to be included.

"With a lot of the questions, I can hypothesise and make guesses, but many things I'll never know. I don't know if that's important. It's enough to have a general outline of their lives," he says.

READ MORE: How Austria’s newest citizens reclaimed a birthright stolen by the Nazis

Howard has had meetings with university archivists, leaders of the Jewish community in Vienna and others who can share details on what life was like when his family lived here. He has based himself in the second district, historically the home of Vienna's Jewish community and the location where Jews included his own family were relocated in 1938.

"There are things I can't begin to know. There is no record of what was destroyed or taken [during the pogroms], so did they lose their home, did something happen to them -- I can't begin to know, but I know the result was that they were moved to the second district."

While staying in the second district, Howard made a surprising and emotional discovery. He and his brother are the only known descendants of their grandparents, but he found out that there is already a small memorial to his family in their hometown.

Outside the building which is their last known address, a small golden plaque -- one of thousands of Stolpersteine (stumble stones) which honour Holocaust victims across Europe -- notes that 121 Jews lived in the building. Just four of them are named, two of them being Howard's grandfather and aunt.

Howard's grandfather Emil and aunt Livia are named on the small plaque outside their last known address. Photo: Howard Goodman

READ ALSO: Stolpersteine: Standing defiantly in communities amid rising tensions

The stone was purchased by the daughter of another victim named on the plaque, an 86-year-old living in Germany, but Howard doesn't know why his family were included.

"I had been to every place I believed my family lived. I had been outside the building, crossed the street and taken photos, but never thought to walk up to the doorway," he says. "When I saw in the database that my family's names were there, I put on my coat, it was about 9 or 10pm, and walked over as quickly as I could. It was quite moving. I already knew where they had lived, when they were born, where they were deported to, but to see it physically like that was really quite an emotional experience."

As well as the Stolperstein, Howard's aunt Livia is remembered in another way: his youngest granddaughter is named after her. Under the new Austrian law, Howard's children and grandchildren are also eligible for citizenship.

"Preserving the Waldmann’s memory for my children and grandchildren is one of the reasons I’ve become an Austrian citizen," says Howard.

Join the conversation in our comments section below. Share your own views and experience and if you have a question or suggestion for our journalists then email us at [email protected].

Please keep comments civil, constructive and on topic – and make sure to read our terms of use before getting involved.

Please log in here to leave a comment.